|

The History of Hapton Valley and other North East and Mid Lancashire Collieries.

Hapton Valley Colliery began life in 1853, when work was undertaken by the Burnley colliery owners, the Exor's of the Late John Hargreaves, who began to sink the two shafts at the pit on the outskirts of Burnley, Lancashire. This area where the pit was to be sunk was well proven for coal, there being scores of shallow workings alongside the Habergham Brook, and in the sides of Hambledon Hill, which in the main were drift workings. The No.1 Shaft at the new pit was 16 feet in diameter, and 271 feet deep. (Those who work in new 'money' will have to work out the metric themselves) The No. 2 shaft was 10 feet in diameter and 263 feet deep.The winding of the coal was done at the No. 1 shaft by a system of endless vertical chains, that raised the coal in the shafts in seven and a half cwt. tubs. Output at the new colliery was said to be around 600 tons per day raised in this manner. The No. 2 shaft at the pit used flat wire ropes and was used for the winding of men and materials. At this time, unusually, all the coal was screened (cleaned) at the pit bottom in a plant installed in the shaft recess. All the waste rock and rubble was sent back into the working where the coal had been extracted and packed into the voids left behind were the coal had been taken.

The new Hapton Valley Colliery soon acquired the name Spa Pit on account of the discovery of a mineral spring around 1818 by Ambrose Eastwood a local farmer. The spring was close by the new pit, and the name adopted. The method of coal extraction at this time at Hapton Valley would have been by pick and shovel working the pillar and stall method of extraction. In August 1908, there was a fire at the pit, which caused the management some grave concern for those men underground. The fire itself was confined to some pithead building, but smoke from the fire was being drawn down the pit via the shaft. Happily all the men were got out through a fan drift driven to the rear of the colliery itself. Around 1910, work was begun on the sinking of two new shafts numbered three and four. Although only a short distance away, these new shafts gave access to a whole area of new ground beyond a fault, or slip in the earth strata. The No. 3 shaft was downcast in ventilation, that is where the fresh air was drawn into the workings, and 18 feet in diameter, and 514 feet deep.

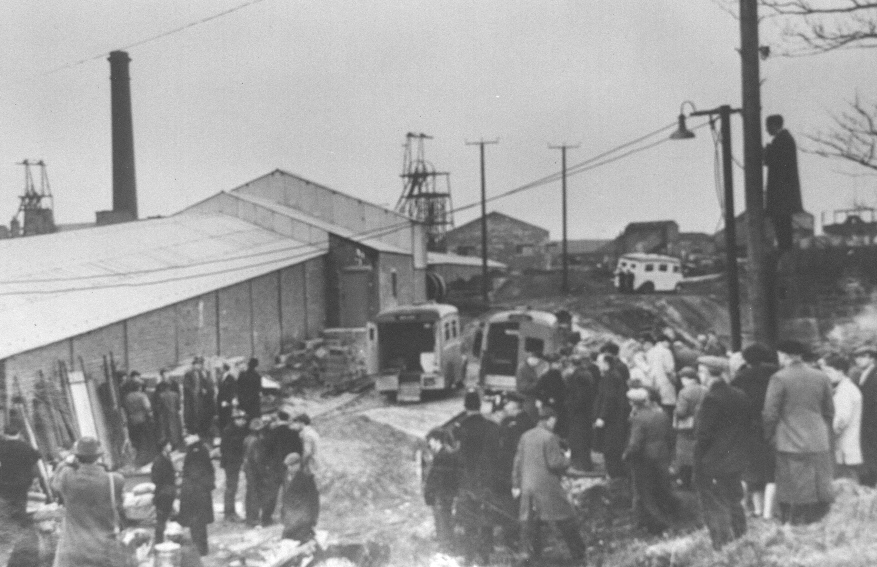

The upcast shaft, where the air was extracted by a fan from the workings (drawing air down the other shaft) was 12 feet in diameter and 488 feet deep. Apart from the occasional strike by the men, notably in 1926, the workings of the colliery progressed as would be normal. An another development at the pit was started in 1940, when work was begun on the new pithead baths. This was soon delayed however on account of the war, and for the duration was hastily converted to use as the pit canteen. In October 1956, work was begun on two inclined tunnels named Wimpys Drifts or the East Side Drifts to open out further areas of virgin ground at the colliery. In October 1957, just as the new seam was being opened out, water in large quantities burst through the floor of the mine and caused extensive flooding. At one time some 700 gallons per minute poured into the mine. Pumps were brought in to stem the flow of water, and eventually the problem was overcome. A surface drift was driven in 1960, and completed in January 1961. The most fateful day in the collieries history of course was the disaster of March 22 nd. 1962, when a total of nineteen men perished. Yet another disastrous problem, any of which might have closed the pit happened in February 1964, when flood water burst through the old Spa Pit shafts, sending millions of gallons into the workings again. This was eventually remedied through powerful pumps. Shortly after this work was begun on the Upper Mountain Seam, but the days of the pit were now numbered. In February 1981, the NCB announced that the colliery was to close, the only workable reserves of coal lay dangerously near the flooded workings of the old Porters Gate Colliery.

VICTIMS OF THE DISASTER

KILLED IN BLAST

BROWN Christopher William, aged 55 years, a driller at the pit,

BULLEN Sampson Henry, aged 44, pit deputy,

CUMMINGS James, aged 19, supply man,

DUNSTON Robert, aged 26 years, a ripper,

FAULKES Stanley, aged 41, filler at coal face,

HALSTEAD John William, aged 55, pit deputy and shotfirer,

HARTLEY George, aged 32, mechanic,

HOWARTH Raymond Ernest, aged 20, electrician,

ISHERWOOD Tom, aged 49, face worker,

McGOOGAN Donald Stewart, aged 28 years, mechanic,

PICKLES Garry, aged 22, electrician,

ROBINSON John, aged 24, face filler,

RUSHTON Donald, aged 33 ripper,

SHUTTLEWORTH Robert, aged 33, filler,

TAYLOR Ronnie Anthony, aged 16, one of two youngest victims, supply lad,

WALSH Benjamin, aged 25, face filler,

DIED FROM INJURIES RECEIVED

BARRITT John Greig, aged 23, electician,

FORREST Joseph, aged 17, supply lad,

TINSLEY Peter, aged 16, appentise electrician,

SERIOUSLY INJURED

ALLEN James, aged 48, conveyor man

BARKER Neville Edward, aged 24, filler,

BULLEN Brian, aged 23 filler,

DYSON George, aged 34, filler,

FISK Alan, aged 24, filler,

GREENWOOD Brian, aged 23, filler,

HEYWOOD John, aged 24, filler,

MADDEN Joseph, aged 46, filler,

MYERS Jack, aged 35, filler,

PINDER John, aged 28, filler,

PINDER Robert, aged 25, brother to John, filler,

WALKER Henry Dransfield, aged 39, filler,

WALSH George, aged 21, filler,

Clifton Colliery Burnley

N.G.R. 833.331

There were three shafts sunk at Clifton colliery each in close proximity. The downcast was 14 feet in diameter and used for pumping proposes. Another shaft, also downcast was eleven and a half feet in diameter, and used for the drawing of the coal and raising the men and materials. The third shaft was nine and a half feet in diameter and 260 yards in depth and was sunk in 1876. This latter shaft, was a cupola or ventilation shaft, and in effect was a chimney. At the bottom of this was placed a furnace, the air which was heated around this furnace was drawn up the copula shaft, which was replaced by fresh air drawn down the two other shafts. Many a bet was won locally by the crafty miners at Clifton, who placed money on a bet that this chimney was the "longest in Burnley". Although the chimney only stood some thirty feet at the surface, the unwary gamblers had to fork out their money when told the chimney in fact went all the way down to the pit bottom some 260 yards. Burnley, being a mill town had many tall chimneys, none could match the one at Clifton pit!. On account of a downthrow fault at Clifton colliery, which passed near the shafts the Arley Mine was worked on two different levels at the shafts. The same seam, was 50 lower in one shaft, than it was in the other. The pumping shaft was 310 yards, while the winding shaft was 260 yards, both to the Arley Mine, the cages here were worked by a steam engine. This engine (steam) was made by Mr. W. Bracwell of Burnley, and had two horizontal cylinders 28in. by 60in. with a 15 foot winding drum. The engine raised four tubs of 9cwt. capacity in each cage on two decks. Automatic devices, prevented overwinding and there was Owen catches fitted in case of a rope breakage. In addition to this, an elastic band was fitted to the ropes to take off the strain when starting off the winding. A smaller engine was situated at the pumping shaft for raising and lowering the men, and was used for secondary access, these ropes also had safety catches fitted. The engine at the pumping pit, installed on the surface was a compound horizontal condensing engine, with two steam cylinders 26in. by 41in. with a 48 in. stroke and was geared 1 to 4. The water raised by this engine was about 560,000 gallons per day, equal to 390 gallons a minute, Clifton was evidently a wet pit!. On the surface six Lancashire boilers 30ft. by 7 ft. supplied steam to all the surface engines at 60lb. pressure. Two steam engines worked underground at the two levels of the Arley Mine to operate an endless chain haulage, or ginney, as it was known locally. The steam for these was also supplied by a Lancashire boiler 28ft. by 7ft. at 80lb. pressure. The Clifton colliery was abandoned December 30th 1955, when the last tub of coal was raised to the surface, by the banksman Mr. T. Bordley. The pit was sunk in 1876 by the Exors of John Hargreaves (Collieries Ltd.) During the 1921 coal strike all the men were out, including the pump men, as a result of this, at the termination of the strike the water at Clifton had flooded the workings to a depth of 70 feet in the colliery shafts. An ingenious method was devised by the pit engineers, whereby the cages were substituted by self emptying tanks. As each tank came to the surface, they automatically emptied their contents which ran away through the small brook at the bottom of Stoneyholme recreation ground thence into the River Calder. This tiny stream is still tainted by "Carr Water" or iron oxide, giving it a rust colour. It was stated that fire-damp or methane gas was never or at least very rarely met with during the working of Clifton colliery. In the early 1950s, Clifton Colliery employed some 200 and odd men on the surface and underground and mined the Dandy and Arley Mines. The colliery was in the National Coal Boards North Western Division, and the pit manager was Mr. A. T. Walton. Very little remains of Clifton colliery, on Oswald street Stoneyholme, is the filled remains of the colliery ginney track tunnel, while between the Stoneyholme school and the motorway is a "turning block" where the ginney changed course. The site of the colliery was landfilled during the construction of the Whittlefield Cutting of the M65 Motorway.

REEDLEY COLLIERY

N.G.R. 839.345

The largest cob of coal ever raised in the Burnley Coalfield came to the surface at Reedley Colliery on the 13th. November 1891, being a full four foot square. Reedley Colliery was sunk in 1879, having two shafts both down to the Arley Mine at a depth of 210 yards. In the pumping shaft was a small two man cage used for maintenance of the shaft and pumps. This cage was raised and lowered by a small single cylinder steam engine, whose early days commenced at the Marsden Colliery that closed in 1873. The Reedley Colliery, Barden Pit locally on account of the adjacent Barden Recreation Ground had underground connections with the Wood End Pit. This shaft was located halfway between the bottom of Barden Lane and the Duck Pits Sewerage Works. The capped shaft at Wood End Pit is still visible to this day. The Reedley pit had the honour of having the first pithead baths in the east Lancashire area, and only the second in the whole country. These were opened in November 1914, under the Coal Mines Act of 1911, clause 77. The building which cost £2,000 were paid for by Sir James Thursby, the colliery being one of the Hargreaves pits. The new baths had facilities for the accommodation of 180 men, and the baths (showers) were made of slate and the floor was concrete in order that they could be "swilled down without any difficulty" The centre of the building employed a pulley system whereby the men raised their day clothes before going down the pit. Pit clothes were placed on the rack in the same manner at the end of the shift. In later years, the Reedley pit became very much an experimental mine, where all the new mining equipment was tested or tried out. Here was introduced the "American System of Mining" that included the use of shuttle cars, roof bolts etc. Roof bolts were universally dis-liked by the Reedley miner, who preferred something he could see holding the roof up above his head, and who could blame him!. Another feature at the pit, was the 558 yard long Sandvic Steel Band Belt conveyor, that carried the coal underground from the pit to Bank Hall colliery coal washing plant. This conveyer worked against a gradient of 1 in 3, and remarkably for the day, weighed the coal at the same time. Reedley pit was also one of the first collieries to employ underground fluorescent lighting.

THORNY BANK COLLIERY

N.G.R.793.307

The Thorny Bank Colliery was a model mine in all respects, both opened and closed by the National Coal Board. The colliery utilised the existing west side drift belonging to the workings at Hapton Valley. A fan was installed here that blew the air into the workings, and in this way the fumes from the diesel locos that worked the surface drift were not drawn in to the mine as it would have been had it extracted. Thorny Bank is known to have had underground connections with both the Hapton Valley and Huncoat Collieries. Geological conditions (and political) spelt the end for Thorny Bank Colliery and the pit ceased production on the 12th. of July 1968.

|